The Rise and Fall of a Powerful Friendship

Throughout Europe's history no man's death would have the monumental impact on the duality and politics involved in the relationship between church and state than that of Thomas Becket; murdered in the hallowed halls of the cathedral at Canterbury, it would be one the greatest scandals of the time, and threatened, not only the rule of King Henry II, but his very grip on sanity. For in Becket, Henry had the greatest of friends and bitterest of critics.

In a mercantile district of London, known as Cheapside, lived Gilbert and Matilda Becket. Gilbert came from a line of bottom of the barrel landless knights, his father having knighted him after the family moved to London from the Norman town of Thierville, France. His marriage to Matilda, the daughter of a long line of Norman merchants that had followed William the Conqueror over to England, may have been an arranged one to keep the families from mingling with the native Saxon population and try and scrape together enough Norman clout to at least stay clinging to the bottom rungs of the nobility. Thomas, the only male of the Becket's 5 children was born December 21, 1119. He would spend his early childhood on the very edges of nobility and respectability, the family with one foot in the commoners world and another in the baronial (lower nobility) world.

|

| Coat of Arms of Richer de L'Aigle |

But their future became a little

brighter as Gilbert accumulated enough good will among the cities upper class

to be appointed a Sheriff of London. As Sheriff, Gilbert would find many looking to give him and his family patronage; 2nd or 3rd sons of local noble houses or nobles of the surrounding areas that do not have the power or money to be considered one of the countries great magnates, all looking to make (or buy) an ally in the local governance of the capital. The most powerful of these, and by all accounts the one who seemed to not have ulterior motives except to be a guiding hand for the up and coming family was Baron Richer de L'Aigle. Though a French Norman, and thus his land titles were back in France, he owned considerable amount of rental property in and around London, and a large personal estate in Sussex. He also had the district honor of being the great grandson of a Norman knight that gave his life to protect William the conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. The Baron took an interest in young Thomas and often invited him to his estate for hunting and hawking. With his financial help and money coming in from Gilbert's own newly acquired rental properties, young Thomas was sent for schooling to the Merton Priory to be taught how to read and write, to learn oratory and debating skills, and study the very basics of math. Later, he was to attend quadrivium classes at St. Paul's Cathedral, the medieval equivalent of earning a liberal arts diploma, studying subjects like music, astronomy, and geometry. Medieval scholars would have the following to say of young teenage Becket:

"His contemporaries described Thomas as a tall and spare figure with dark hair and a pale face that flushed in excitement. His memory was extraordinarily tenacious and, though neither a scholar nor a stylist, he excelled in argument and repartee. He made himself agreeable to all around him, and his biographers attest that he led a chaste life."

|

| Theobald of Bec |

|

| Bologna University |

The next step of his education was to give him a taste of the outside world, and so was sent to Paris for a year at the age of 20. But his trip would be cut short and he would be summoned back home after a fire raged through London not only destroying his families rental properties but tarnishing his father's reputation just enough to lose his office of Sheriff. To help the family out in this dire time, Thomas started work as a clerk of one of his father's remaining rich allies, Osbert Huitdeniers, a well off commoner who ran a private accounting office for the city. But Baron Richer would not see the boy wasted in such a low social class position, and so arranged for him and Gilbert to meet with the powerful Archbishop of Canterbury, the head of the Catholic Church in England. Gilbert and the Baron, using the Becket's family ties to Thierville, persuaded the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theobald the Bec, whose family was also from Thierville, to take the boy into his household as a clerk. It did not take long for the Archbishop to note how clever and intelligent Thomas was and paid to have him and another young man of promise, John of Salisbury (whose written work later in life would have him declared post-humorously one of the preeminent political philosophers of the age) study civil and canon law at University of Bologna, in Italy. As a fellow student, John would say of Thomas:

"His elegance was enhanced by vivacity.... He had excellent manners and was a good talker. Clearly he had the ability and the will to please: he was a charmer. He also possessed very acute senses of smell and hearing and a good memory. Such endowments make a little education go a very long way. He was undoubtedly intelligent, alert, and responsive. Once he realized that he had to make his own way he became extremely ambitious."

While in Italy, Thomas made several trips to the Vatican on assignments from the Archbishop and each time, in the words of the archbishop, "preformed his duties to perfect diligence". So upon Thomas's return to England Archbishop Theobald appointed him Archdeacon of Canterbury. Over time because of his faithful and exacting service he would also be named, even though not ordained as a priest, as a lead member of the clergy at both the Cathedral at Lincoln and St. Paul's in London. No matter how many duties or assignments Theobald placed on Thomas, his energy and efficiency never diminished, in fact it was all the elder clergyman could to do to keep up with his servant. This quality gave the Archbishop a stroke of inspiration; only one other man in the kingdom has displayed Thomas's level of vigor in duty, the new King, Henry II.

Archbishop Theobald had been recently counseling the new king on what government advisory and bureaucratic positions needed to be filled and who should fill them. But knowing that the King, with his boundless energy, would be off and away to multiple locations and hotspots a week, he would need someone to corral and supervise all these men and at the same time have the energy to match the Kings. Theobald himself was already and old man and his duties to the church made such travels too difficult. So in 1155 he introduced Henry to his household clerk, Thomas. To say the two hit it off right away would be a gross understatement as within days of meeting and carousing together Thomas was named head of the King's household, and treasurer of the royal families finances. The appointments infuriated Queen Eleanor, but nothing enraged her more than when Thomas was made Lord Chancellor, a position that gave Becket not only the royal seal, but enabled him to speak and command with the King's authority in Henry's absence; all she could do was watch as her dreamed ambitions of being a true and equal co-ruler were yanked out from under her. She would never forgive Henry for it, and it came out in ruthless and vicious ways later in their lives, well after Becket's death. Some claim she could not take out her anger sooner for fear of Becket unraveling any schemes she could come up with.

But for now, for the next couple of years, it would be great time for Henry. If Henry needed money for a war in Wales or France, Thomas found it. If Henry needed some governance system to ensure unbiased law enforcement, Thomas created it. If the nobles or bishops, including his former patron Theobald, acted out, Thomas gained their compliance. The English side of Henry's realm was the model of smooth and successful governance, operating with surplus in the treasury coffers and not a hint of any complaints from the peasantry. And though the nobles all took issue with someone as low of birth as Thomas having so much power and the confidence of the king, none would dare voice their concerns at court. For Henry and Thomas had developed a relationship well beyond professional, they had become the best of friends. The chroniclers of the time would say of the two "they had but one heart and one mind". and "Often the king and his minister behaved like two

schoolboys at play." The two would spend hours partying and feasting together; some say Thomas would gleefully help Henry sneak his mistresses in and out of whatever castle or estate they happened to be at, even right under the nose of the queen, thinking it a sort of game. Practical jokes between the two were also a common occurrence: One story goes that as they were riding along the streets of London on a Autumn evening, when Henry noted a beggar on the street, "Do you see that man? How poor he is, how frail, and how scantily clad!

Would it not be an act of charity to give him a thick warm cloak.". Becket agreed but kept riding on. Henry in response dragged Thomas off his horse and forceably removed his cloak, giving it to the beggar, saying he will make sure to tell everyone of Thomas's charitable nature. The two laughed about it on their way back to the palace. But Thomas would have his payback as the next morning Henry awoke to find all his hunting cloths had been given to the staff by Thomas. Henry would have to meet his hunting entourage that morning in nothing but his night gown and a long flowing formal robe, the kind Henry hated to wear even when occasion called for it. His lords all looked worried and anxious, waiting for the famed temper to erupt, but then Thomas burst out laughing at the site and the king followed suit, releasing the tension. Henry even broke convention and tradition to show his love and trust in Thomas when he sent his son, young Henry, to foster at Thomas's estate while he was away. The tradition was nobles would foster their children with other nobles of equal or greater power to spread good will and trust, so Henry giving charge of his son and heir to Thomas instead of one of the great magnates of the realm like Robert de Beaumont or Ranulf of Chester, was considered quit shocking. Again much to the disapproval of his wife Eleanor and his aging mother Matilda. The boy himself was grateful for the placement as later in life he noted it meant he was never to far from his home in London and able to see his mother more often than if he had been shipped to some other lords far off castle, he was even quoted as saying "Becket showed me more fatherly love in those few days than my father showed me in my lifetime."

For 6 long and prosperous years things went on like this, bringing Henry and Thomas great joy, frustrating the queen and the queen mother, perplexing the nobility, and bringing stability for the entire nation. But it would hit its peak in the spring of 1161. Theobald of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the Church in England , Papal Legate, and Thomas's mentor and patron passed away. Henry wasted no time in putting Thomas's name forward to fill the position. The past couple of years, while the rest of his realm ran smooth, one group had been a persistent thorn, the bishops. Though Theobald had been an adviser at the start of his reign, the old man had started to embolden his subordinates into obstructionist policies, claiming church privilage in resisting paying taxes or abiding by the rule of secular courts. Thomas had always worked things out between the crown and the bishops, but now here was an opportunity to cut out any and all negotiations with the religious sect of his realm. If his own Chancellor and best friend were head of the bishops and have the ear of the pope the church would be in his pocket permanently. Henry made the necessary diplomatic overtures to Rome, promising more tithing, land for monetarists and cathedrals, even a pledge to provide soldiers and knights for the protection of Outremer if needed. Pope Alexander III consented that the nomination can be brought before the King's council for a vote. Henry knew he had the nobility on his side: despite what they thought of Becket, having someone that could tilt the balance of power in favor of secular rulers over the church would benefit them to much to let their prejudices of Thomas low birth get in the way. The Bishops were another matter; a faction of senior bishops, lead by the bishop of London, who up until now was thought of as the natural successor of Theobald, resisted. A series of back door deals and talks occurred bringing the clergy to the kings side. All but the bishop of London who held out the longest, but then unexpectedly changed his mind. Some believe members of the nobility (perhaps with or without the Kings knowledge, no one knows for sure) threatened the bishop for his vote. Surprisingly, the last obstacle was Thomas himself who at first was inclined to refuse the post, pleading that Henry do not put their friendship in jeopardy:

"I know your plans for the Church, you will assert claims which I, if I were archbishop, must needs oppose."

But Henry would not relent, he believed Thomas would put his position as Chancellor and their enduring friendship first above any responsibilities of Archbishop. So on June 2, 1162, Thomas Becket was ordained as a priest and on June 3rd made Archbishop of Canterbury. Their relationship would immediately take a nosedive as the once vain and gregarious lover of fine wine and woman Thomas Becket seemed to transform in a matter of days into a contemplative, pious, solemn, man of the cloth, dedicated to his role in the church and to an aesthetic lifestyle. Becket no longer attended the King's feasts or hunting expeditions. He more than doubled the amount Theobald had expended on the poor and invited large groups at a time into his home to have them fed and to wash their feet. He viewed his past lifestyle as sinful and as penance wore an uncomfortable hair-shirt under his monastic or bishop garb and refused to sleep in a bed, instead sleeping on the cold stone floor. He even took up the orthodox practice of scourging himself or having one of his priests or monks do it to him.

|

| Clare Family Crest |

Henry and his nobles did not think anything of this at first, sure the King was sad that he could not spend the time with his friend like he use to, but thought all this was to detract from Thomas's naysayers who were critical of his appointment as archbishop. But the first sign of strain would come shortly after, when Henry was away excreting his control over his French domains. Thomas had embarked on a campaign for the church to regain control of some lands that the church had reluctantly ceded to the crown under Theobald and then to have them taken off the secular tax rolls. This ran him into conflict with the powerful magnate Roger de Clare, 2nd Earl of Hertford, who owned an estate in Kent that was on land the new Archbishop claimed was once the church's. When Thomas sent a messenger to the Earl trying to push his authority, the Earl had the messenger eat the letter. Another incident occurred when tax collectors were shooed away by priests

when trying to collect a tax called a Sheriff's Aid, to help supplement

the income of law enforcement. Thomas claimed that since this was a tax not directly sponsored or approved of by the church it was optional and people could not be forced to pay it. Incidents like these and a few others reached Henry in France and so he made his way back to London to try and smooth things over. Thomas and Henry, meeting for the first time in almost a year since Thomas's ordination, in the city of Woodstock, Oxfordshire, had an intense and almost combative negotiation on the accumulating conflicts between England's secular rulers and spiritual leaders. It is at this meeting that Becket resigned his position as Lord Chancellor and gave Henry the great seal back, feeling the position and honor bore to much of a conflict of interest with his duties as Archbishop. They were able to resolve the issues through compromise but both came away feeling dissatisfied; more so the king who was feeling betrayed by a friend.

|

| Constitutions of Clarendon |

Knowing this would not be the end, both Thomas and Henry spent the next year maneuvering themselves to have the advantage when the next church and state conflict came upon them. The next great debate was the church's role in the justice system. The tradition since the rule of Henry's grandfather, Henry I, was that clergy accused of minor crimes would be tried by a clerical court, not by the King's justice. The bishops for years have been arguing for an expanding role of the church's courts, but for the most part this had been dismissed. But now under Becket, the church took that idea of expansion to a whole new level; that the right to be heard in the church's courts instead of the secular courts was extended to not just clergy but any in the church's employee. Deacons, clerks, and other lay people of the church could now opt to be judged by the church instead of the courts. Becket went even further and extended it to farmers who worked church owned grounds and craftsmen who were regularly commissioned by clergy. The final straw for Henry was when Becket declared that clergy could not be tried in any secular court at any time for any crime, even for major crimes like treason or murder. The king summoned the magnates and bishops to assemble at the palace of Clarendon to address the crisis. The demand was made that the jurisdiction system be restored to his grandfather's traditions and that the church's court be scaled back to what it was meant to be. Negotiations went on for days and progress was made thanks to the mediating skills of Thomas's old patron Baron Richer de L'Aigle, now a senior statesman and adviser to Henry. Thomas relented and his expansion of the church's court was limited to allow clerk's and deacons to also opt for church ruling for minor crimes, all other changes Becket had made would be rolled back. In exchange certain rights of the accused would be upheld and when it came to the sentence of capital punishment a man cannot be humiliated and degraded in public and then executed "for it would be though he is being punished twice." The final agreement was written in a document now known as the Constitutions of Clarendon, which would become one of the founding documents of English Common Law and would be one of the inspirations for the much later Magna Carta.

Thomas though, only a few months later, rejected the agreement and again started pushing for the expanded rights of the clergy and lay people in the employee of the church. Henry was furious and was looking for any reason to be able to have Becket arrested and brought before him. Both men plead there cases to Pope Alexander III, but the Vatican was determined to stay neutral, as they saw this an internal English matter and asked that the two of them find a way to resolve it peacefully. Henry made his next move when he found out that Thomas was to take a trip to the Vatican. One of the stipulations of the Constitutions of Clarendon was that bishops, being partially high ranking members of governance need the King's permission to set foot into enemy territory; as Thomas's route would take him across France and Henry and King Louie were again at odds with one another, Henry used the coming departure as an excuse to have Becket arrested in violation of the Clarendon Accord. But once at North Hampton were the king was currently holding court, to Becket and the king's surprise, trumped up charges having nothing to do with the archbishop's trip were stacked against him, including illegal confiscation of land owned by John Marshal, Baron of Marlborough, and accusations (most likely orchestrated by agents of the Queen) that he had embezzled large sums of money from the treasury while acting as Chancellor. The Archbishop denied all charges saying the land Marshal is referring to was on loan to him from the church and thus the church had a right to take it back and that every penny was accounted for before he resigned as Chancellor, but was willing to pay the money anyway to resolve the issue. The king was seriously considering the offer in hopes of perhaps salvaging his former friendship when the Robert de Beaumont, as the new Chancellor, and at the urging of the queen, demanded Thomas be tried for treason as well, for his contact with the French. Henry refused Thomas's offer in light of his new Chancellor's accusations which he could not ignore our else look weak and biased to the rest of the Magnates and so decreed Becket should stand trial.

Becket saw the writing on the wall, even if Henry was inclined to see reason, the barons under the influence of the queen would not rest until they had his head. He snuck out of North Hampton castle and made his way to France. Becket lived out the year at a monastery of the Cistercian order in Ponitgny, waging a propaganda campaign against Henry, continually writing to like minded English nobles, the Pope, King Louie and the German Holy Roman Emperor Fredrick I. Meanwhile back in England the Gilbert Foliot, Bishop of London, came to an uneasy understanding with Henry and took up must of the duties of the archbishop but not the title. When Becket, still technically archbishop, started excommunicating many of Henry's advisers through writ, Henry threatened to start closing Cistercian monasteries all over England unless they kicked Becket out. Becket appealed to the pope for help, asking him to threaten Henry with excommunication since only the pope can excommunicate a King. Pope Alexander was sympathetic to Becket's cause but did not want to alienate Henry who was an ally against the Holy Roman Emperor's ambitions for northern Italy. So instead he granted Becket the title of papal legate giving his already excommunication decrees more weight. Henry put even more pressure on the Cistercian's and started threatening Becket's friends and allies in England. So Becket left the monastery and was granted asylum by the French King, to stay at his estate in Sens. The Pope saw now, with the French King being involved, how dire the situation was the getting and feared the potential of it exploding into a war and so ordered both men to stand down, to make no more escalations until a special council he was to convene could decided on the issues. For 4 years things remained in limbo as the papal legalists mulled the events that lead to this. To see an end to the stalemate King Henry sent Bishop Foliot, Roger of York, Hilary of Chichester, and Roger of Worcester, to Normandy to negotiate a deal with the papal commission, who were then to present it to Becket. Terms for Becket's return were hashed out and included promised amendments to the Constitutions of Clarendon. But when the deal was presented to Becket he flat out refused saying that the commission was selling out the church's rights and authority and he did not recognize their authority to negotiate on his behalf, he than proceeded to excommunicate Bishop Foliot, accusing him of being "a wolf in sheep's clothing". This was followed by excommunication of more of King's advisers and the powerful Earl of Norfolk without warning as a way to compel the King himself to see him face to face, and if not than excommunication of more English magnates and bishops would come. With the help of the Archbishop of Rouen the highest clerical authority in Normandy, Foliot had the pope rescind his excommunication and censure Becket from anymore impromptu excommunications.

|

| crowning of Henry the Young King |

Meanwhile back in England King Henry had come to a decision on how to split up his Empire among his children. He knew even if he named one of his children as king of England, without a clarification of which child received control of which realm to administer the French King could use it as an excuse to re-exert control over the Angevin and Norman French lands. So to Richard, being his mothers favorite, he named Duke of Eleanor's ancestral lands of Aquitaine and he named him Count of his father's ancestral lands of Anjou, Geoffrey would become the Duke of Brittany, the the title of Count of Bois would still be held by Theobald V and his heirs, and his eldest son Henry would overlord all of them as King of England and Duke of Normandy. But to his youngest, John, there was nothing left, thus earning him the long time moniker Lackland. He also saw an opportunity in all this to to humiliate Becket. It was customary in England going back to the early days of unified Saxon rule that an heir apparent be crowned as king in waiting at the Canterbury Cathedral by the Archbishop, this in theory was to help ensure a smooth transition as a replacement king would be ready to go at the moment of the king's death. But as there was no current Archbishop of Canterbury as far as King Henry was concerned, he had his son crowned Henry the Younger, crown prince and future king of England, by the archbishop of York, Roger de Pont L'Évêque, and with the assistance of the Bishop of London, Foliot, at St. Paul's on June 14, 1170. It was a scandalous move that divided not only the nation by the clergy of almost the entire continent in whether Henry had the right to alter such a tradition.

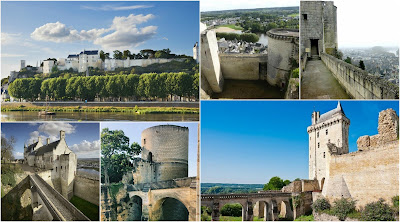

Becket again appealed to the Pope, explaining that this could have far reaching repercussion to the balance of power between kings and the church if Kings could dictate the circumstances of coronations, one of the few levers of power the church had to wield over royals. The Pope agreed and allowed Becket to place the whole of England under the threat of interdict, the right of the church to refuse a people of sacraments and other services of the church. This was the final move that would finally force Henry to meet his old friend Thomas face to Face. In July Thomas and Henry met outside of the Angevin ancestral home, the castle at Angers. Their two entourages hung back as the they rode ahead in a field to talk in private. Those watching from a distance say they fought as only two close friends could, screaming at each other at one point, laughing the next, sobbing to each other at other points. 20 years of emotions laid bare that day and an accord was reached with both men returning to their fellows visible shaken. Henry stayed behind in France, and headed for his French capital of Chinon, while Thomas wasted no time to head back to England to Canterbury to resume his duties as archbishop.

But upon his return Becket's first move was to take account all those in the high ranking clergy that had collaborated with the Henry against him in his absence. He again excommunicated Bishop Foliot and several others for siding with the secular power over their duties and loyalty to the church. Bishop Foliot immediately sent word to Chinon of what was happening. Henry was well into the wee hours of the morning feasting and drinking all night in Christmas celebration, when the news was delivered. Accounts say the king was driven into a torrent of emotion, laughing, crying, howling in both despair and anger. At one point even cursing God for not removing the love he has for Thomas from his heart. Many of his guests left not knowing how to handle the situation, all but a few close advisers and a retinue of household knights that were also considered close friends stayed behind to console their conflicted king. It was in this pitiful drunken deranged state that the King uttered those famous and fated words:

"What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and promoted in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk! Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest."

The King was ushered off to bed by his concerned knights, to sleep of the wine and the heart break. While the king slept his remaining guests whispered about what they could do to help their troubled lord and what exactly if anything the king had meant in his outbursts. Henry locked himself away in his personal chambers, refusing to see anyone, including his own family members, giving no official word of what his next move would be. On December 29, 1170 a few short days after that troubling party, four of the kings loyal household knights, Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy and Richard le Breton, the same knights who at that party were trying to comfort their king and to sleep, showed up at Canterbury, with an unidentified royal clerk. They left there weapons outside as custom before entering a church and walked in Becket in the middle of preforming evening prayer, called vespers, demanding that the Archbishop accompany them to Winchester to await the kings arrival, to account for his shabby treatment of his friend and lord. Becket refused, claiming on a spiritual level his duties to the church must come before his former friendship and on a secular level, they being low-born landless knights held no sway over an archbishop. He told them that if Henry wished for their relationship to improve he must come there himself and repent of his sins against the church and its clergy. Becket wished the knights a goodnight and proceeded with nightly duties. The knights left without a word, grabbed their weapons and stormed back into the cathedral. When a monk by the name of Edward Grim confronted the knights about bringing weapons into a church he was thrown aside and wounded. Becket came rushing to see if the young man was okay, when he was attacked. Grim tried to shield the archbishop, trying to block the knights approach with the staff and cross, but again was shoved to the side. In Edward Grim's testimony of the events he states:

"The wicked knights leapt suddenly upon him, cutting off the top of the miter which the unction of sacred chrism had dedicated to God. Next he received a second blow on the head, but still he stood firm and immovable. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows, offering himself as living sacrifice, and saying in a low voice, "For the name of Jesus and the protection of the Church, I am ready to embrace death." But the third knight inflicted a terrible wound as he lay prostrate. By this stroke, the crown of his head was separated from the head in such a way that the blood white with the brain, and the brain no less red from the blood, dyed the floor of the cathedral. The same clerk who had entered with the knights placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr, and, horrible to relate, scattered the brains and blood about the pavements, crying to the others, 'Let us away, knights; this fellow will arise no more"Up for debate is whether King Henry truly sought this outcome, was his drunken outburst an illusion to cover up the fact he was ordering the death or at least the kidnapping of an archbishop. Or was it simply ravings of drunken distraught man that were taken to seriously by loyal sycophants. Whether he was cognizant of what he was saying or not I do not believe he wanted to see Thomas murdered, certainly not in such a brutal fashion. The argument could be made that he may have nudged them towards kidnapping, thinking if they do it great, but if they don't get the hint that's fine also. But again I take issue with this, as a number of accounts say he had been heavily drinking during his Christmas feast and just how clever could he have been well into his cups. Historians can debate all they want, but we will probably never know.

News of the assassination of Thomas Becket spread like wildfire through the whole of England and France. Henry was with the Bishop Arnulf of Lisieux discussing next possible political steps to submit to the papacy against Becket, when the news reached him. This is another notch for those like me that believe Henry had no clue about what was going to happen; if Henry was expecting Becket to be kidnapped or murdered soon, why seek counsel with Bishop Arnulf about how to make a case against Becket to the pope. Seems like their are other ways to cement an alibi than rely on yet another clergyman. The bishop would later report that Henry would not stop crying for three whole days and had refused food and dink to the point were Anulf's monks had to force feed him water. Henry's enemies , including King Louie used the murder as propaganda against Henry's interests and trying to turn the christian world against the Henry's rule in England and France. But none was more vocal than ecclesiastical poet and writer, William of Blois, whose writing and speeches started forming a cult around Becket, convincing a segment of the people that Henry had knowingly slaughtered a living saint. He even wrote to the Pope trying to convince him of Henry's culpability in the matter:

"I have no doubt that the cry of the whole world has already filled your ears of how the king of the English, that enemy of the angels... has killed the holy one... For all the crimes we have ever read or heard of, this easily takes first place - exceeding all the wickedness of Nero."

William and his followers were slowly turning the people against Henry's rule. It did not help that the four knights who had committed the deed fled to the Scottish border with the aid of some of the magnates who were known to be harsh critics of Becket's. Meanwhile, Henry had not lifted a finger either way, he had for a time become a shut in, and even when he was out walked as though in a trance. Some say he could sometimes be seen pleading with Thomas for forgiveness as if the archbishop was their in the room with him. The whole of England looked to be a powder keg ready to go off, with the King of France just waiting, licking his lips. But the French king would over play his hand and Henry's sons' revolt against their father, orchestrated by the French King and the vindictive Queen Eleanor, would knock the king out of his stupor. On those events, we will have to wait when we continue Henry's story. As for his Becket problem, instead of trying to suppress or break apart the forming cult and the calls for martyrdom, Henry embraced and championed it. He publicly admitted that while he never desired his friend's death, his drunken, ill-chosen words brought it about. He sent bishop Arnulf to the Vatican to be his advocate and plead not only his case but also the case for canonizing Thomas as a saint. The pope granted Thomas sainthood in February of 1173 and in May sent Henry the Judgments of Avranches, a list of demands that Henry was to meet in order to obtain absolution over Becket's death. First, that Henry was to recruit, equip, and pay for the travel of 200 knights for the holyland, second, the Constitutions of Claredon were again amended this time to state that clergy, deacons, and clerks were to be tried by the clerical court in all matters except murder, treason, and arson. Third, that all churches, cathedrals, and monasteries were immune to taxation for the rest of Henry's reign unless the bishops freely gave to the treasury. Fourth, the four knights were to come to the Vatican to stand in judgement before the pope. And last, the king must make a penance of his choosing that would be satisfactory to the bishops of England. It was this last part that historians debate whether it was public theater, another calculated move to bring in more supporters among the peasantry or if it was a heart felt attempt to appease his friends spirit. I see it both, but you be the judge. The penance he proposed to his bishops would be more than they would have asked for, and all made under public spectacle. To start he dedicating a new nunnery in Barking to the memory of St. Becket (making sure to have the public realize he played a part in the archbishops canonization) and naming Becket's sister Mary as abbess. But more shocking and dramatic was his act of contrition on July 12, 1174. Setting out from the outskirts of Kent his day was described as such by a local monk named Gervase:

another monk by the name of Ralph de Diceto added:"He (Henry II) set out with a sad heart to the tomb of St. Thomas at Canterbury... he walked barefoot and clad in a woollen smock all the way to the martyr's tomb. There he lay and of his free will was whipped by all the bishops and abbots there present and each individual monk of the church of Canterbury."

"He spent the rest of the day and also the whole of the following night in bitterness of soul, given over to prayer and sleeplessness, and continuing his fast for three days... There is no doubt that he had by now placated the martyr."He would try to visit the tomb at least once a year for the rest of his life, often seen talking and laughing at the stone effigy as if having the kind of conversations with his friend all those years ago. Henry was never the same after that, he was noted as being less cheerful unless in the midst of one of his schemes. He was more cynical and even quicker to anger than ever before. And no one would ever feel a genuine bond of friendship from the king.

However, any hatred or disloyalty that the peasantry of England may have had for Henry evaporated. For the rest of his reign he would have them all to himself; not one magnate or bishop, nor any of his wayward children or their scheming mother would ever be able to take the love of the people on this side of the channel away from him. A man that has shown true contrition by suffering in an almost Christ like fashion. And had their new champion, his admitted enemy, raised up into sainthood. In the eyes of the highly religious every-man of the age What a magnificent leader they had, who could rule as magnanimously or as pious as he. King Louie, the Queen, and Henry's children, in their effort to demonize the Angevin king, gave him cause to create a completely opposite atmosphere about him. As for the four knights Henry did not hesitate to have them found, arrested and sent to Rome. There they pleaded their case that they believed they were doing their duty not only as servants of the king but as friends of a comrade in grief and distress. Pope Alexander granted them mercy and absolution in exchange for a 14 year commitment to crusade in the holy land. Their deeds their would bring about the English knightly Order of St, Thomas founded by Richard the Lionheart.

St. Thomas would become one of England's most revered figures, even to this day. Pilgrimages would be made from across Europe to see his tomb at Canterbury. In fact, in the famed anthology Canterbury Tales by Chaucer, it is Becket's tomb the varies narrators are heading to to pay homage. Today a sculpture of 4 swords (representing the 4 nefarious knights) hangs above the very spot were the saint's body laid dead. St. Thomas is venerated in both the Catholic church and the Anglican church with a feast day of December 29th. He his the patron saint of secular clergy, of the cities of Oxford and Portsmouth, of those that stand up to authority in just causes, and those that defend Christians from abuses from secular leaders. Paintings, icons and statues of St. Thomas are often depicted not only with the signature halo around his head like most saints, but also sometimes with a sword running through his head as a symbol of his martyrdom. And besides the innumerable, churches, chapels, shrines, abbeys, and monasteries named after him, one of the largest interfaith non-profits is named for him as well, the The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty a legal and educational institution dedicaed to free expression of religious traditions. His conflict with King Henry II will be recounted throughout the rest of history every time there is a debate in the western world about the relationship between church and state. From Henry VIII spit with Rome to the authority of the Spanish Inquisition, from the American founding fathers principles of separation of church and state to the evolving role of the clergy in the french revolution and Napoleonic wars; each time Becket's tale is made a factor in the discussion.

Like I said with my Julius Caesar posts I like adding movie and TV images as I believe it helps with seeing these historic figures as real people more than looking at old paintings and tapestries. The movie images used for this post are from the 1964 film, Becket, starring Richard Burton as Thomas and Peter O'Toole as Henry, which won an Academy Award for best screenplay. The movie has many minor inaccuracies and omissions in the chain of events and one major one in portraying Becket as of Saxon descent, resentful of how Henry treats his people as one of his motivations, which is wrong. However, it is an amazingly well acted film, with both Burton and O'Toole having been nominated for an award for best actor (both being beaten out by Sidney Poitier for Lilies of the Field, so its understandable why neither one of them one) and O'Toole winning the Golden Globe best actor award. You will be especially in awe of O'Toole's performance, he really gives off the unbridled cyclone of emotions that I could imagine Henry must have been feeling through all this. O'Toole's manic Henry plays as a great juxtaposition to Burton's Thomas, a more melancholy and contemplative man, but through a talented performance, with skilled use of his eyes and turns of the head, you can see how much he is torn inside, how much he regrets having to go against his long time friend. So for historic purity I give it a 5, but for characterization of our two main subjects I give it an 8. Its supporting cast is meh, but I think that has more to do with the over shadowing nature of the two main characters and the actors portraying them rather than any fault of the rest of the cast. The film was also nominated Academy awards for best Picture, director, costuming, and editing; so not a bad bit of pedigree. Its set pieces and costuming are pretty good for the time the film was made, both winning BAFTA awards. And if, like me, you don't mind that classic percussion and brass heavy, melodramatic orchestra style of score found in old school Hollywood period pieces I really recommend it as a great piece of cinema, just don't go using it as a source for your next history class essay.